AI Inflation: How Compute Costs Are Reshaping Tech’s Margins

The growing cost of compute and its impact

Introduction

Artificial intelligence is redefining not only what technology can do but also how much it costs to make it work. The computational resources required to train and deploy advanced models have grown from a background infrastructure item into one of the largest expenses in the technology sector. As models become larger and more capable, the financial burden of compute has begun to reshape the structure of technology margins and the distribution of value across the sector.

A recent cost-model study estimates that the amortized cost of training frontier models has grown at roughly 2.4 times per year since 2016 [1]. Meanwhile, surveys of enterprise AI spending show that average monthly budgets rose from about US $63,000 in 2024 to an estimated US $85,000 in 2025, representing a 36% increase in compute and infrastructure outlays [2]. These data illustrate that compute is no longer a minor infrastructure line item but a strategic cost of goods sold. This article analyses how compute-cost inflation is compressing margins, transforming pricing dynamics, concentrating supplier power, and generating strategic and policy-relevant implications for firms, investors, and regulators alike.

The escalating cost of training AI models

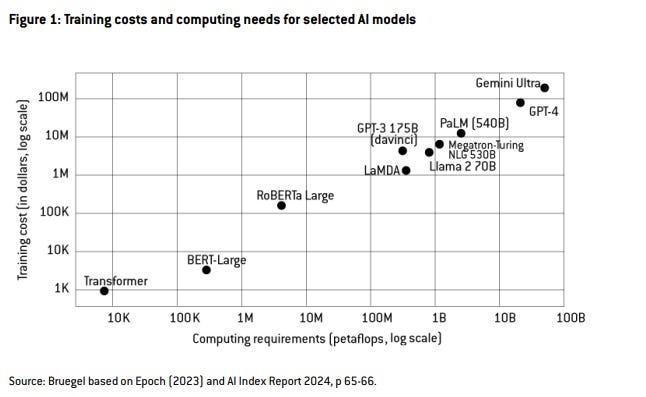

Training advanced AI systems has become increasingly capital-intensive. The academic cost-model study referenced above reveals that for the most compute-intensive “frontier” models the amortized development cost has grown at roughly 2.4x per year since 2016 (90% confidence interval 2.0x to 2.9x) [1]. In the same study hardware accounted for roughly 47–64% of total cost; staff and research & development (R&D) between 29–49%; and energy consumption just 2–6% [1]. Supporting this, a working paper by Bruegel found that training costs for top-ranked generative AI models in late 2024 edged toward US $200 million [3].

These figures highlight a critical shift: where training investment once resembled a large but manageable project, it now resembles industrial-scale infrastructure deployment. Only organizations with deep pockets, favorable supplier relationships or scale advantages can invest in frontier-model development. Meanwhile, the amortized cost of training becomes a capital-cost burden that must be recovered across the lifetime of model deployment. In consequence, compute cost has moved from being a background input to a defining determinant of competitive advantage and margin potential.

Continuous cost pressure from inference workloads

While training cost is high, the ongoing cost of inference (model serving) presents a continuous margin pressure. Many AI-driven firms report that inference workloads may dominate lifetime compute cost, because models deployed in production see large cumulative usage. One enterprise survey shows average monthly AI budgets are rising and cost management is becoming a key concern [2]. While the cost of running large language models is falling rapidly (roughly 10x per year for equivalent performance) AI services still face significant infrastructure costs per use. Factors such as longer prompts, higher-quality outputs, and the need for faster or concurrent responses can increase compute and energy demands [4]. As a result, firms face a structural shift: the amortized cost of training frontier models, combined with ongoing energy, hardware, and operational expenses for inference, creates continuous margin pressure for AI-enabled services [1].

Margin compression in software and cloud business models

The shift in unit economics is material for technology businesses. In the conventional software-as-a-service (SaaS) model high margins were built on fixed costs amortized across many users, and marginal cost per user was near zero. With AI however, marginal cost per user is non-zero, variable and usage-dependent. If product pricing fails to track compute cost, margins erode. Access to affordable compute is becoming increasingly important for AI businesses, as inference costs, while falling rapidly, still represent a significant operational expense [4]. Larger players who can negotiate scale or integrate vertically maintain stronger margin headroom; smaller players face higher per-unit cost and shrinking margin flexibility.

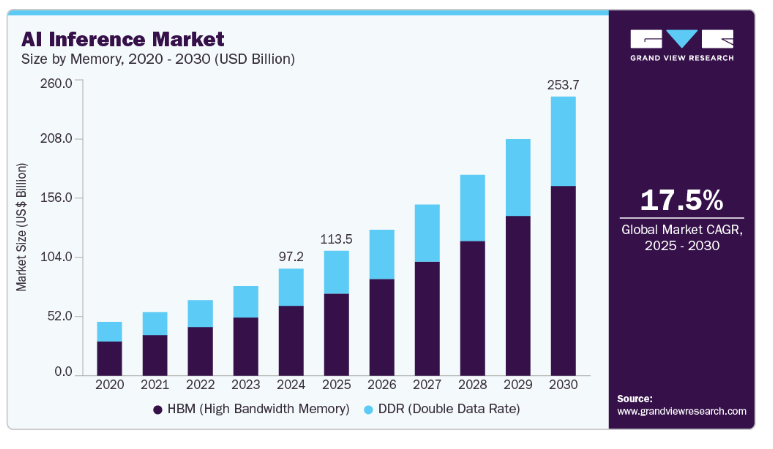

Market estimates place the AI-inference market size at approximately US $97.24 billion in 2024, with projected growth to US $253.75 billion by 2030 (compound annual growth rate ~17.5%) [5].

As workloads shift to AI-dedicated infrastructure the cost pressure falls more heavily on firms lacking integrated infrastructure advantages. Empirical margin data support this: Monetizely reports that AI-centric companies typically operate with gross margins in the range of 50-60%, compared with 80-90% for top-tier traditional SaaS firms [6]. In effect, the era of near-zero marginal cost per user in software may be closing; for AI-enabled services the cost of compute is a material component of margin structure.

Supplier concentration and strategic infrastructure dynamics

Compute-cost inflation is shaped by supply-side dynamics of compute infrastructure. The market for AI accelerators, specialized chipsets, systems design, cloud deployment, and data center real estate is highly concentrated. Firms with scale are able to secure favorable pricing, long-term supply contracts, and vertically integrate. The high fixed-cost nature of build-out (accelerators, cooling, power, real estate) means incumbents benefit from economies of scale. While exact valuations vary, the data center sector supporting AI workloads is already substantial and expected to grow significantly in the coming years [3]. Training costs for frontier AI models have risen from USD $1,000 in 2017 to nearly USD $200 million in 2024, highlighting the steep infrastructure investment required [3]. For firms lacking scale, spot-market access to GPUs, rented cloud instances, or limited capacity can mean higher hourly costs, less predictability, and reduced margin flexibility. This imbalance reinforces scale advantages, raises barriers to entry, and shifts margin dynamics in favor of infrastructure-rich players.

Operational and business-model responses

Faced with rising compute costs and margin pressure, firms adopt a variety of strategies, including deploying smaller, quantized, or distilled models for production and reserving larger models for high-demand tasks. A benchmark study found that larger LLM inference tasks can consume significantly more energy per token or inference request, and factors such as model size, hardware generation, and sharding configuration play large roles in driving that energy cost [7]. Firms negotiate dedicated capacity, co-invest in infrastructure or adopt on-premises clusters to reduce exposure to variable rental pricing and spot-market cost fluctuation. Instead of flat subscription models, firms adopt pricing structures based on token-count, prompt/response length, latency/quality tiers or premium features to reflect underlying compute cost. Price-analysis commentary suggests AI-enabled SaaS margins are adjusting from ~85% to ~60-70% unless pricing changes [6]. Firms secure long-term commitments with hardware and cloud suppliers, integrate vertically across software/hardware stacks or co-own infrastructure to stabilize cost bases and predict margin behavior. Each of these responses involves trade-offs: higher capital investment, slower time-to-market, more complex engineering or higher product pricing. Scale remains decisive in which firms can pursue these options at competitive cost.

Digital-Service Inflation: A New Cost Layer

Compute-cost inflation is spawning a new form of digital-service inflation, where underlying production costs for AI-enabled software rise and can translate into higher pricing or squeezed margins if costs are not absorbed. Because backend compute is becoming more expensive, firms confront three possible responses: increase prices, reduce feature sets, or absorb cost and accept lower margins. Furthermore, organizations report gross-margin erosion tied to AI workload costs: one survey finds that 84% of enterprises report at least 6% gross-margin erosion due to AI infrastructure costs [8]. These findings suggest that part of compute-cost inflation may pass through to consumers: via higher subscription fees, token-based pricing or premium charges for compute-intensive features. Hence compute-cost inflation is not only an internal margin issue, it has implications for how digital services are priced, consumed and scaled.

Investment, market structure and valuations

The compute-cost dynamics described carry significant implications for investment, market structure and valuations. Firstly, compute-cost inflation means that capital intensity, margin discipline and scalability are now more critical in AI-business evaluation. Firms with unclear margin pathways or that cannot commit to infrastructure investment may face lower valuation multiples. Secondly, infrastructure providers (hardware vendors, cloud platforms, data center operators) stand to capture increasing value as compute demand expands and smaller players pay higher per-unit costs. Thirdly, as compute becomes “infrastructure-like” in cost and strategic nature, policy, regulation and regional development factors increasingly matter for firm strategy and valuation. For example, the cost of securing power, cooling, real-estate and long-term supply contracts influences capital budgeting, risk assessment and competitive advantage. Thus, compute-cost inflation reinforces scale advantages, raises barriers to entry and affects both startup viability and incumbent strategies.

Policy, regulatory and systemic considerations

The rising cost of compute and its infrastructure implications raise policy and regulatory questions. Because compute infrastructure is energy-intensive, regionally concentrated and controlled by a narrow set of suppliers, issues of energy grid capacity, infrastructure planning, supply-chain resilience and competition policy become salient. Firms that build or rent infrastructure for AI training and inference need to pay close attention to power, space, and cooling capacity, and negotiate favorable pricing or commitments to secure profitability [4].

Moreover, competition policy might need to consider supplier concentration in the compute stack similarly to how regulators treat telecommunications or utilities infrastructure. Transparency in compute-cost reporting, infrastructure subsidies and strategic hardware investment are emerging issues. In effect, compute-cost inflation elevates AI infrastructure from a business concern to a policy-relevant domain where corporate strategy, investment and public policy intersect.

Conclusion

Compute-cost inflation is reshaping technology-business economics and service-pricing dynamics. Compute is no longer a background input to software margin models; it is a strategic cost driver influencing pricing, margin structure and scale advantage. Firms that approach AI purely as a software layer, ignoring compute cost, risk margin erosion, slower growth or competitive disadvantage.

To succeed in a compute-intensive future, firms must design for the cost of compute: optimize model architecture, align pricing to compute usage, lock in infrastructure cost bases and anticipate supplier dynamics. Investors must reassess margin expectations, capital intensity and infrastructure risk across AI business models. Policymakers must recognize compute infrastructure as strategic, incorporate transparency and competition into planning, and treat digital-service inflation as part of broader economic inflation dynamics.

In short, as AI permeates the economy, compute-cost inflation becomes a material force: margins will increasingly depend not just on what you build, but on how efficiently and at what cost you serve it.

References

The rising costs of training frontier AI models | Cottier, B., Rahman, R., Fattorini, L., Maslej, N., & Owen, D. (2024), arXiv

https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.21015

The State of AI Costs in 2025 | CloudZero (2024)

https://www.cloudzero.com/state-of-ai-costs/

The tension between exploding AI investment and limited compute | Martens, B. (2024), Bruegel Working Paper 18

https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/2024-10/WP%2018%202024.pdf

Welcome to LLMflation: LLM inference cost is going down but infrastructure cost is not | Andreessen Horowitz (2024)

https://a16z.com/llmflation-llm-inference-cost/

AI Inference Market Size & Trends to 2030 | Grand View Research (2025) https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/artificial-intelligence-ai-inference-market-report

AI Pricing in 2025: How much does AI cost in 2025 | Monetizely (2025)

https://www.getmonetizely.com/blogs/ai-pricing-how-much-does-ai-cost-in-2025

From Words to Watts: Benchmarking the Energy Costs of Large Language Model Inference | Samsi, S., Zhao, D., McDonald, J., Li, B., Michaleas, A., Jones, M., Bergeron, W., Kepner, J., Tiwari, D., & Gadepally, V. (2023), arXiv

https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.03003

2025 State of AI Cost Governance Report | Mavvrik AI (2025)

https://www.mavvrik.ai/state-of-ai-cost-governance-report/